Read this site’s featured article.

Webbon’s

interview – 5

Remember, there are ten episodes of this interview. This is the fifth.

At the beginning, Joel Webb quotes a text that blames only Judaism for liberalism. I call this self-righteous monocausalism, since it’s obvious that Christians are the biggest culprits (even early Church Fathers criticized Jews for their selective compassion, saying it wasn’t universalist but ethnocentric). As always, this pair seems to have no idea that the doctrines of the religion they profess have axiological consequences.

Later, Nick Fuentes says he believes in the historicity of Christian child sacrifices by Jews in the Middle Ages: something I don’t believe was historical. But Fuentes is right to criticize Napoleon for “emancipating” the Jews in Europe, something that didn’t happen in Russia (in my opinion, because the Russians didn’t go through a Renaissance and an Enlightenment that eventually transformed into neochristianity).

Webbon says: “All false religions lead to hell.”

That’s worse than any toxic message from Jews on Netflix or any other mass media outlet. I challenge anyone who doubts this to read my autobiography, Hojas Susurrantes, and still claim that the doctrine of eternal damnation wasn’t worse than Jewish subversion for the mental health of white men. The most ironic thing about this is that this pair ignores the fact that the core of the New Testament was written by Jews.

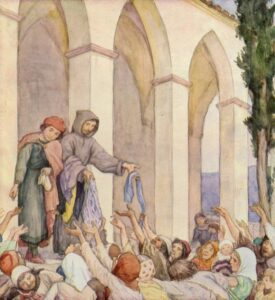

But shortly afterward, Fuentes said something very true: that the message of forgiveness is absent in the Old Testament, that it only appears in the Gospel (for example, with words like “forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing”), and that the Old Testament speaks more of exterminating enemy peoples.

What Fuentes ignores is that the Old Testament message is the right one if the Aryans were to adopt it (as Himmler’s SS did). This pair takes the out-group altruism inspired by Christianity for granted: it’s a morality that Christians don’t even question (nor do atheist neochristians).

In this fifth instalment of the interview, we again note what Gaedhal once said: the dissident right is more primitive than liberal Christians, insofar as they wholesale ignore academic studies of the New Testament that differ from fundamentalist dogma (for example, Webbon speaks of the Transfiguration as if it were a historical event).

The blatant dishonesty comes soon after, when Webbon says, “Christian faith and reason are not at odds with one another.” If they were honest, these Christians would be familiar with the critical literature on New Testament historicity written since the time of Reimarus.

The blatant dishonesty comes soon after, when Webbon says, “Christian faith and reason are not at odds with one another.” If they were honest, these Christians would be familiar with the critical literature on New Testament historicity written since the time of Reimarus.

I make these comments from that series to show how lost American white nationalism is, even though Webbon isn’t one of them (Fuentes does consider himself a white nationalist). This episode proves it.

Later, Webbon asks Fuentes what transformed the healthy antisemitism of yesteryear into today’s pathological philosemitism. Fuentes blames modernism and liberalism. I wonder if Nick knows that we call liberalism “neochristianity” on this site? (new visitors who haven’t read our quotes from Tom Holland’s book should read them now).

Shortly after, Webbon says: “The engine of liberalism is egalitarianism: the complete flattening of every natural distinction…” Although Webbon mentions race and gender, he sees the speck in someone else’s eye but not his own. Following the destruction of the Greco-Roman world, it was Judeo-Christians who introduced egalitarianism into European culture. (Although both detest the word “Judeo-Christian”, they also ignore that early Christians were mostly Semites from the Roman Empire: so the term is legitimate.)

Note that, when they later discuss Protestant currents like dispensationalism, some factions of that current accept the salvation of Jews—that is, no post-mortem damnation for the chosen people. However, they don’t extend this courtesy to so-called “pagans” (those who refuse to worship the god of the Jews). How can this pair not realise that this type of doctrine will sooner or later develop a philosemite theology (not only Protestant, but also Catholic after the Second Vatican Council)?

Fuentes then says that the foundation of liberalism and modernity is the concept of the human psyche as a tabula rasa, a “blank slate”: that we are all born as persons, and therefore equal. He fails to realise that this belief was spawned by elemental Christian teachings: that, unlike animals, all humans are born with a “soul”, and that “God” doesn’t distinguish between “souls”.

Do you see why we call liberalism neochristianity? Later, they both agree that we must wait for the Jews to convert to Christianity and that, in the meantime, Jews have rights and shouldn’t be mistreated. Compare this to the Germans of the last century, who transvalued Christian values into values similar to those of Titus and Hadrian during Rome’s wars against Judea.

Do you finally understand what our slogan means?

Umwertuung Aller Werte!

Transvaluation of all values!

Missiles

If a submarine with nuclear warheads were to fall into my hands, before the forces of evil could neutralize me, I would try to destroy the System by launching missiles at New York (especially where Jewish financial power is concentrated), Washington (whoever wins the elections always ends up being a lackey of Israel), Jerusalem (nothing I hate more than seeing Western leaders at the Wailing Wall with a kippah), Tel Aviv (so that Muslims can then commit a second holocaust when radiation clears), Los Angeles at Hollywood (so that they don’t poison white men any further with their movies), Moscow (as revenge for what the Russians and their Asian troops did during the Hellstorm Holocaust), Beijing (so that the Chinese don’t emerge victorious after the skirmish), Mecca (nor the Muslims), Berlin (with the American Diktat, after 1945 the Germans have been suffering from a Stockholm syndrome to the nth degree; nuking them at the seat of their anti-Nazi power would help them break the spell), Paris (they deserve it because that’s where atheist neochristianity arose), London (imperative to nuke the city that boasts the most billboards of English women with nigger partners in the streets), and finally the Vatican because of what Nietzsche says on the last page of The Antichrist.

by Gaedhal

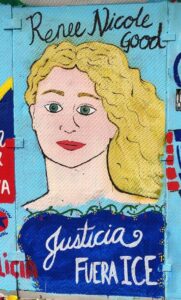

I didn’t want to comment on the killing of Renée Nicole Good. First off, it has nothing to do with me. The only link Good has to Ireland, is that she was a missionary in Northern Ireland.

I didn’t want to comment on the killing of Renée Nicole Good. First off, it has nothing to do with me. The only link Good has to Ireland, is that she was a missionary in Northern Ireland.

And the people who are shooting your ideological enemies in the face, today, are the same people who could very well be shooting you in the face tomorrow. Hence, the governor of Florida, Ron DeSantis (R) actually came out against this shooting. As I said before: one probably has to have a personality disorder to join either the police or the army. Perhaps police forces and armies are necessary in this world; however, in my view they are necessary evils.

In Northern Ireland, we have an anomoly. We have a police force that is secret; we have a police force that is armed; we have a police force that allows its officers to carry weapons, whilst off duty.

Now the police service of Northern Ireland is not ICE, not by a long shot; however, there are parrallels. All of the other police forces in the British Isles are mostly unarmed.

However, the term “U.S. Citizen” has suffered from hyper-inflation, due, in large part to immigration. When the U.S. was a white racial republic, the term “US citizen” actually meant something. The founders were explicit: the republic was founded for their posterity. However, a citizenship that anyone can claim; well, that becomes sorta worthless. If anyone can become a U.S. citizen, then U.S. citizenship is sorta worthless.

Liberals—those to the right of Leftists, in this context—largely turned a blind eye to non-citizens being denied constitutional rights, even though the courts said that the norms of the U.S. constitution applied everywhere that the U.S. was the sovereign or de facto sovereign power. Obama never shut down the concentration camp at Guantanamo bay. Although he did attempt cosmetic changes in an attempt to bring some of what goes on there in line with constitutional norms.

Also, in a polarized society, one’s political opponents no longer inhabit the same moral universe. At the beginning, the Left and Right, in America, had a shared vision of what America is was and should be, however, they differed on the issue of federalism or antifederalism. Today, there is no agreement between Left and Right on just about anything. Thus appeals to Renée Good’s being a “U.S. citizen” from the Left are utterly worthless, given the polarisation of America.

I really only have an expressable opinion on this one aspect of this controversy: appeals by Liberals and Leftists to Renée Good’s being a U.S. citizen, and why they are likely to fall upon the radical right’s deaf ears.

In Ireland, “Irish citizen” is actually a sarcasm, describing some invader who was magically alchemised into his/her becoming Irish by way of a magical piece of paper, to wit, an Irish Passport.

And, of course, as my good friend Alex, who has since gone to be with the ground, “magic paper” such as passports are merely the secular version of “magic water”. Indeed, the idea of a birth certificate might have actually come from the Roman Catholic Baptismal certificate.

Catholics believed that magic water could turn the inhabitants of Africa into Christians—i.e. civilized white men, but with a different skin tone—and Liberals believe that the alchemy of magic documents, such as passports, can more or less accomplish the same thing. Catholics believed in the magic of catachesis, and, as Revilo P. Oliver points out: Liberals believe in the magic of education. Education, very often, to Liberals, is a snake oil that will cure whatever ails society.

Thus, we are still under the tyranny of Christian axiology; of Christian assumptions; or, as Oliver might have put it, the reformed Church of Marxianism has superceded the unreformed Catholic and Protestant Churches.

Booklets, 3

As I’ve already said, I originally didn’t want to post my private comments on some booklets published under the auspices of the Third Reich because I didn’t want to openly criticise National Socialism: I kept those criticisms to myself. Now that I better understand the dark times, and considering that my duty is to yearn for a dawn in the Aryan collective unconscious, I believe I must exhume my notes written on the blank pages of these booklets.

On July 19, 2021, for example, in the booklet shown in the image, I wrote:

I barely see the first paragraph and a problem arises.

Since I am a priest of the Fourteen Words and not a Nazi, the likely fact that this booklet won’t be anti-Christian (cf. also my fundamental difference with white nationalists) suddenly occurred to me.

The booklet is composed of ten articles by various authors. Then I read the following sentences from the first article, written by Erich Maschke. It doesn’t matter that the rest of the articles by the other nine authors didn’t contain passages I consider offensive. What I want to point out are the contradictions of National Socialism between those who represented its exoteric face and the more esoteric enlightenment on Christianity held by Hitler and his inner circle.

Erich Maschke wrote:

…the heathen Prussians. By force of arms must the Brothers subdue or drive out the heathen tribes… War against the heathen was the highest duty, the greatest sacrifice which a man could offer. [page 5]

…this forcible Christianizing of the Baltic countries of Prussia, Latvia and Estonia… The Prussian tribes were fought until they were subdued and accepted the Christian faith. [pages 6-7]

Maschke wrote these things apparently approving of the forced conversion of these Germanic pagans. On the blank page at the end of the booklet I wrote:

It’s worse than what I wrote inside the cover!

I was so surprised that it motivates me to start a new series for WDH, which we could begin with “Why Nazism Failed, Part 1.” And I would continue if I find this type of message in the other thirteen booklets I bought and will read (except for Sieg der Waffen which doesn’t have any bad messages).

I never expected this. It’s becoming increasingly clear that the priest is not a Nazi, although he still considers Hitler the man whose birth should replace that of the mythical Jew whom the fools of American racialism still worship.

Sometime later, I wrote on the back cover in black ink: “What I wrote in this booklet with blue ink [quoted above] is devastating. I’ll see now if I’ll report this to WDH…”

But I didn’t do it in 2021.

Groupthink

This is a response to Ben’s most recent comment.

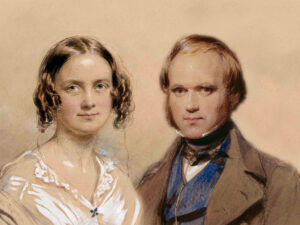

Groupthink really shocks me. In private correspondence, Charles Darwin said that the Negroes would become extinct because, being inferior, white people would exterminate them. The opposite happened because he didn’t foresee how Christianity had conquered the Aryan collective unconscious.

The best example of monstrous groupthink that comes to mind is precisely that of Darwin’s wife, Emma. Like a typical stupid woman who conforms to the prevailing worldview, she once became upset about the criticism that the torture of hell wasn’t eternal (of course: she was taught the opposite as a child)!

The best example of monstrous groupthink that comes to mind is precisely that of Darwin’s wife, Emma. Like a typical stupid woman who conforms to the prevailing worldview, she once became upset about the criticism that the torture of hell wasn’t eternal (of course: she was taught the opposite as a child)!

The difference between Emma and Charles is fundamental to understanding what’s happening. The vast majority follow groupthink, whether it’s the aberrant theology of the past or the suicidal anti-racism of today. Modifying the archetype that possesses the collective unconscious is no small feat. And the sad thing is that no one is fighting it now except us. (White nationalists are still possessed by the current archetype, ortherwise they would become pragmatic exterminationists like Darwin.)

Incidentally, I was extremely bothered to see, on my last visit to the UK, how young whites fraternised with Negroes in restaurants and cafes.

Webbon’s

interview – 4

After the eighth minute Nick begins to talk about his ideology: “America First.”

Right away there’s the problem, because “America” isn’t just made up of white people, but millions of people of colour.

But of course: Fuentes is a Christian. Compare that to the priest with the 14 words, “The Aryan comes first,” which leaves no room for misunderstanding. But that’s not Nick’s starting point.

Some time later Fuentes said he might vote for a black man running for president.

Do you see why all that “America First” is rubbish, if not outright treason?

Shortly after, Webbon says that abortion is wicked, even for blacks; and before that he said there would be 25 million more Negroes in the US if abortion were prohibited! Nick agreed.

Compare this treacherous bullshit to the Nuremberg Laws.

In the rest of the conversation they said pertinent things about the JQ, but what was indicated shows that Christians aren’t useful for preserving the Aryan race from ongoing extinction.

Chapter III: The spinning of the web

Just as the spider weaves his silky web, to lure flies into the larder of his banqueting hall in order that he may at his leisure, pick the flesh off their bones, so deceitful ideals are cunningly woven by dexterous, political spiders, to capture and exploit swarms of human flies.

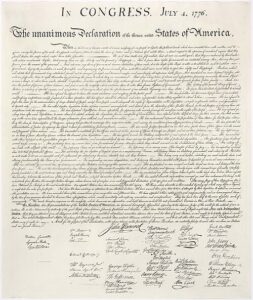

What are the grandiose paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence, but the weft and woof of a dazing spider-web? And what are the American People but the flies that have been cleverly entangled in its gossamer meshes? For over a century this ‘Declaration’ has been the parchment divinity or all public orators, from the curbstone dervish at the street corner, to our Elective Monarch in the White House. Every 4th of July, Americans habitually scream themselves hoarse over its sounding generalities: making the welkin ring with tin-horns, giant fire-crackers, flag-idolatry, brass bands, toy pistols and herd- bellowing generally. Although the great majority of them are mental and physical dwindlings, poverty-stricken, and property-less yet how insanely they delight in amusing a sardonic world with their loquacious flamboyant charlatanry. ‘We are sovereigns and equals’ is their everlasting Barmecide chorus. ‘Sovereigns and Equals!’

In all lunatic asylums may be found inmates who fancy themselves kings and queens, and lords of the earth. These sorrowful creatures, if only permitted to wear imaginary crowns and issue imaginary commands, are the most docile and harmless of all maniacs.

As for the American People of today, Is not their written constitution but a cunningly constructed straight-jacket—their moral codes, padded prison-cells: their statute laws handcuffs and leg-irons—their Captains of Industry keepers and turnkeys in clever disguise? One hundred years ago they ostensibly commenced ‘independent’ operations with the richest continent on earth as their private property—their subscribed capital; and during the whole of that period, have they not been as busy as so many relays of draught beasts-of-burden, pumping the tremendous natural wealth out of their home soil, and pouring it over-sea, into the cess-pools of Europe?

Is not that the work of lunatics? They smashed and splintered the wooden political yoke of an English king and then proceeded to rivet around their necks a brand new yoke of bolted steel, which they forged especially to fit themselves: and which they dignified under the name of ‘Constitutional Freedom’.

Is not that also the work of lunatics? Cursed indeed are the harnessed ones! Cursed are they even though their harness be home-made—even though it tinkle musically with silver bells—aye! even though every buckle and link and rivet thereof is made of solid gold.

How absurd of men to hurrah over their ‘glorious political liberty’ who have not even been able to retain possession of the substantial products of their own laboriousness. After a century of ‘constitutional progress,’ ten per cent of the population are absolute owners of ninety-two per cent of all the property.

Now, O reader, Are not these things the outward and visible sign of organic dementia?

Netflix, etc.

Since my sister lent me her Netflix account so I could watch Breaking Bad, I decided to watch the first few minutes of other series and movies filmed during the darkest period in Western history.

Seriously, anyone who watches that stuff regularly as if it were legitimate entertainment is a person with a xenomorph in their brain, so I had a daring idea that I won’t carry out: to start reviewing each of those things and, at the first subversive message, stop watching.

For example: there’s a series about Latin American drug traffickers that begins with a scene of the drug lord Pepe Escobar. I barely watched the first few minutes and I thought to myself: “Those lands should be conquered by pure Nordics. Since the writers don’t propose turning Latin America into New Scandinavia, the series’ message is bad”, and I stopped watching it in the first scene of the first episode.

Something similar happened to me with one of the most famous Batman instalments: a film that even some white nationalists love (that’s why I said yesterday that they too have the xenomorph amalgamated in their brains). The moment I saw that they want to prosecute a gang of criminals through the American legal system I interrupted because, in a sane world, they would simply be executed like the Nazis would (the American Constitution, its laws and legal institutions are, naturally, xenomorphic).

I could say something similar about other films or series, of which I only tolerated watching a few minutes of each. But with what I’ve said, it’s clear what my reviews would be like for 100% of what’s shown on Netflix, HBO, in theaters, on free or pay television channels, not to mention the millions of accounts on various social media platforms.

Do you finally understand what I’m saying in the featured post?

The aspirant to the priesthood of the sacred words will find it hard to swallow, but only the day after tomorrow belongs to us, as Nietzsche would say; some of us will only be born posthumously…

Yes: we priests are premature births of a future yet to be verified: a future whose arrival is uncertain, but which I will strive to bring about through my work (that’s why I named the publishing house I hope to found Daybreak).

Breaking

Bad, 3

Tucker Carlson asks a beautiful blonde who is behind the destruction of the white race through mass migration. Neither of them knows the answer.

The typical white nationalist would say it is the Jews, but that doesn’t explain things like white suicide in the Roman Empire through gradual miscegenation that culminated in Constantinople, or what the Spanish and Portuguese did in the Americas since the 16th century. Nor does it take into account the beginning of the repudiation of anti-miscegenation laws in some US states long before the Jews took over the country.

As I have already said, to understand what archetype has taken hold of the Aryan collective unconscious, it is necessary to look at the cultural aspect, specifically bestsellers. Ivanhoe in the 19th century idealised Jewry; Ben-Hur portrayed the Romans as the bad guys and the Jew as the good guy, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin portrayed the black man as the good guy and the Dixie landowners as the bad guys. These super-bestselling novels have something in common: they weren’t authored under Jewish influence but by Christians who vehemently subscribed to Christian ethics.

In our century, the above-mentioned novels have lost their power to X-ray the soul of the contemporary white man. But now we can do so with the television hits that the white masses loved: the zeitgeist of our century.

Yesterday I finished watching, skipping what I already remembered from the first time I saw the series, Breaking Bad including the sequel movie, El Camino: where Jesse Pinkman is the main character (Walter White had died at the end of Breaking Bad). I don’t want to dwell much on my repetitions but, like the novels mentioned (one European and the other two American), the good guy in the film perfectly portrays what I have called neochristianity on this site.

The scenes that bothered me the most were when Jesse, in a fit of St Francis-like madness (Francis gave away the clothes his father made to the poor of Assisi), gave away to the people on the street the millions of dollars that Walter had worked so hard to earn. But worst of all is that, prior to that neo-Franciscan fit, half of Jesse’s millions were destined, as he asked his lawyer Saul, for a Hispanic woman and her mestizo son…

The scenes that bothered me the most were when Jesse, in a fit of St Francis-like madness (Francis gave away the clothes his father made to the poor of Assisi), gave away to the people on the street the millions of dollars that Walter had worked so hard to earn. But worst of all is that, prior to that neo-Franciscan fit, half of Jesse’s millions were destined, as he asked his lawyer Saul, for a Hispanic woman and her mestizo son…

There’s the answer to Tucker’s question!

As I said, regarding Tucker’s question a white nationalist would automatically blame Jewry, exonerating the white man. From our POV, one must take into account the great hits of Western culture as X-rays that portray the particular archetype that has taken hold of the Aryan psyche. And it is clear that this archetype is Christian ethics, which, although authored by rabbis in the form of the New Testament, has been internalised by the Aryan to the very core of his being (which is why I recently used the image of the xenomorph stuck deep in the throat of a white man).

This is what white nationalists don’t want to see. But if they don’t see it they will become extinct.

There is no point in criticising Jewry if one doesn’t perform a radical operation on one’s own soul to remove the xenomorph (the Bible in a nutshell: “Old Testament exterminationism for me; universal love for thee”). And this is done, of course, by transvaluing all Christian values including things like raping the Sabine women to create not a New Jerusalem but a New Rome; genociding the people of Jerusalem without Titus’ contemporaries feeling the slightest remorse, and even the (occasional, not normative) recreation with ephebes for centurions who haven’t seen their wives for years and want to take certain liberties with their cupbearers before battle.

All of this—mass rape of women to found Rome, occasional acceptance of pederasty, or having feelings opposite to those of Jesse Pinkman in a genocidal campaign—is completely alien to white nationalists precisely because they have the xenomorph embedded in their brains.

For Americans, who unlike Europeans were born into Christianity, it will be very difficult to transvaluate Xtian values.

But it is the only path to salvation.

All values

The concept of transvaluation is not fully understood. I doubt that even the Christian and neochristian (i.e., atheist) racialists who visit this site understand it.

If we take into consideration what I recently said in my previous post in the context of Greco-Roman pederasty, we could educate visitors with this reasoning:

During Rome’s wars against Judea, Titus was given the responsibility of putting an end to the rebellious kikes, a task he carried out successfully after besieging and conquering Jerusalem in 70 c.e., whose temple was looted and destroyed by his troops in the burning of the city. His victory was rewarded with a triumph and commemorated with the construction of the Arch of Titus.

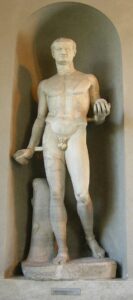

They even made a statue of him modelled on Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (79-81 c.e.), which is in the Vatican Museum. As can be seen in the statue, a pope didn’t tolerate penises and ordered all the statues in the Church’s custody to be “castrated”.

They even made a statue of him modelled on Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (79-81 c.e.), which is in the Vatican Museum. As can be seen in the statue, a pope didn’t tolerate penises and ordered all the statues in the Church’s custody to be “castrated”.

The Nazis didn’t finish revaluing all values. It was a process that in the 1930s was just beginning. If National Socialism had developed over the last eighty years, there might already have been attempts to sculpt the Aryan warriors of our century inspired by Polykleitos or other classic sculptors. But at the time, national socialists still carried the shame or guilt inherited from Judeo-Christianity: it would have been inconceivable to sculpt statues of Hitler naked even if, like Titus, he had won the war against the Judea of our times.

Transvaluing includes putting naked statues of every Aryan hero in public squares, as the Greeks and Romans did, and not having them hidden and “castrated” by deranged popes in Judeo-Christian enclosures.

Sometimes I wonder, besides myself, who has transvalued all Judeo-Christian values?