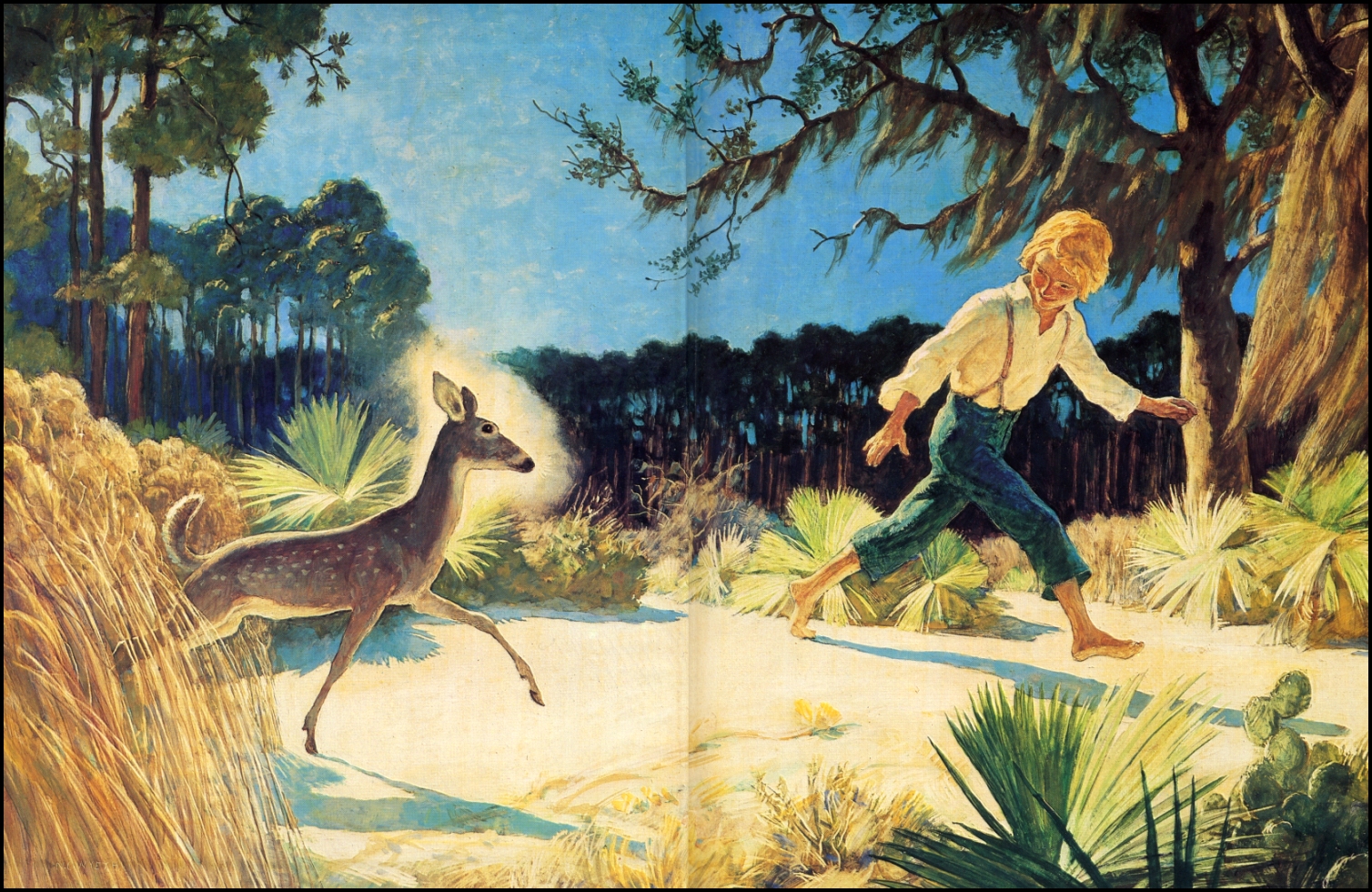

The Yearling is a 1938 classic authored by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (1896-1953); the above is an illustration by Newell Convers Wyeth (1882-1945) of a scene in the novel.

Recently I read The Yearling for the very first time in my life—the very same old copy with Wyeth’s moving illustrations that so much inspired me as a young child, though never read it.

Now, decades later, I finally read it and the story was quite a shock. I’ll try to offer my views on it now that, for many years after my childhood, I investigated in-depth the subject of parental-filial relations.

My interpolated comments below, in brown letters:

Penny Baxter lay awake beside the vast sleeping bulk of his wife. He was always wakeful on the full moon. He had often wondered whether, with the light so bright, men were not meant to go into their fields and labor. He would like to slip from his bed and perhaps cut down an oak for wood, or finish the hoeing that Jody had left undone.

“I reckon I’d ought to of crawled him about it,” he thought.

In his day, he would have been thoroughly thrashed for slipping away and idling. His father would have sent him back to the spring, without his supper, to tear out the flutter-mill.

“But that’s it,” he thought. “A boy ain’t a boy too long.”

As he looked back over the years, he himself had had no boyhood. His own father had been a preacher, stern as the Old Testament God. The living had come, however, not from the Word, but from the small farm near Volusia on which he had raised a large family. He had taught them to read and write and to know the Scriptures, but all of them, from the time they could toddle behind him down the corn rows, carrying the sack of seed, had toiled until their small bones ached and their growing fingers cramped.

Although it is apparently nonsense to try to ponder into the soul of a fictional character—precisely what I’ll do—, I believe that Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, hereafter referred to as “Marjorie,” must have observed something like this in real life.

Folk who lived along the deep and placid river St Johns, alive with craft, with dugouts and scows, lumber rafts and freight and passenger vessels, side-wheel steamers that almost filled the stream, in places, from bank to bank, had said that Penny Baxter was either a brave man or a crazy one to leave the common way of life and take his bride into the very heart of the wild Florida scrub, populous with bears and wolves and panthers. It had been understandable for the Forresters to go there, for the growing family of great burly quarrelsome males needed all the room in the county, and freedom from any hindrance. But who would hinder Penny Baxter?

It was not hindrance. But in the towns and villages, in farming sections where neighbors were not too far apart, men’s minds and actions and property overlapped. There were intrusions on the individual spirit. There were friendliness and mutual help in time of trouble, true, but there were bickerings and watchfulness, one man suspicious of another. He had grown from under the sternness of his father into a world less direct, less honest, in its harshness, and therefore more disturbing.

He had perhaps been bruised too often.

As will be seen by the end of the novel, the way he was treated by the preacher will have consequences in the way Penny treated his only son. As to the mother, Marjorie tells us that “The babies were frail, and almost as fast as they came, they sickened and died.”

It is a pity that nobody in the white nationalist scene is familiar with the work of Lloyd deMause, since this pattern of many babies that became “sick and died” is common among mothers that actually are not doing their best for the survival of their offspring. Again, it would be nonsense to psychoanalyze a purely fictional character, but I am pretty sure that Marjorie observed actual happenings in the real world before writing her most famous book.

Marjorie describes the main character, the surviving son, thus:

The mirror showed a small face with high cheek bones. The face was freckled and pale, but healthy, like a fine sand. The hair grieved him on the occasions when he went to church or any doings at Volusia. It was straw-colored and shaggy, and no matter how carefully his father cut it, once a month on the Sunday morning nearest the full moon, it grew in tufts at the back. “Drakes’ tails,” his mother called them. His eyes were wide and blue. When he frowned, in close study over his reader, or watching something curious, they narrowed. It was then that his mother claimed him kin.

It must be noted that Jody’s skinniness (I would call it “leptosomatic physique”) was direct inheritance from his father, since Marjorie writes about the two, “There was room enough for the two thin bony bodies.”

The first adventure in The Yearling was a failed attempt to kill a large bear who had been causing havoc among the family’s farm animals. Three dogs joined the hunting with father and son but one of the dogs fled in panic while the other two charged heroically at the wild beast while Penny tried to fix his broken shotgun.

A whine sounded in the bushes. A small cringing form was following them. It was Perk, the feice. Jody kicked at him in a fury.

As a child I’d never had expected this behavior from the cherubic boy I saw in Wyeth’s illustrations. Penny patiently explained his son that even a coward dog should not be mistreated.

Penny was a good man. Later he and his son Jody visited their rude neighbors, the Forresters, to get a new shotgun. Jody’s only friend in such a remote place was a Forrester kid called Fodder-wing. Handicapped since birth, this kid is presented in the novel as an animal lover. The following is a dialogue between Fodder-wing and Jody:

He said, “Hey.”

Fodder-wing said, “I got a baby ‘coon.”

He had, always, a new pet.

“Le’s go see it.”

Fodder-wing led him back of the cabin to a collection of boxes and cages that sheltered his changing assortment of birds and creatures. The pair of black swamp rabbits was not new.

The timeframe of novel is the aftermath of the American Civil War. The above dialogue caught my attention because it shows the jump of empathy or “psychoclass” (again, a deMause term) from those times and our current times.

A year ago my niece received a wonderful gift: a little rabbit. I observed her pet’s behavior for a while and concluded that it is cruel to put these absolutely cute creatures in cages. They need open spaces and feel real soil beneath their limbs. Presently rabbit lovers know that their pets must be free at least four or five hours a day, preferably in the backyard or home’s garden. Many rabbit owners allow their pets move freely in their flats if they cannot afford gardens. Compared to them, even the most sensitive member of the Forresters belonged to another class, empathetically speaking.

After the scene of Jody and Fodder-wing’s diverse pets outdoors, the next scene occurs indoors, in the Forrester home:

Buck said, “Leave the young un stay, Penny. I got to go to Volusia tomorrow. I’ll ride him by your place.”

“His Ma’ll rare,” Penny said.

“That’s what Ma’s is good for. Eh, Jody?”

“Pa, I’d be mighty proud to stay. I ain’t played none in a long while.”

“Not since day before yestiddy. Well, stay, then, if these folks is shore you’re welcome. Lem, don’t kill the boy if you try out the feice afore Buck gits him home to me.”

They shouted with laughter. Penny shouldered the new gun with his old one and went for his horse.

Even while Penny was, metaphorically speaking, two quantum leaps above the Forresters as to what elemental empathy is concerned, in my opinion he was not empathetic enough.

If I had a beautiful young son like Jody, I would never leave him spending a night among the masculine, Neanderthalesque neighbors even if I had no reason to suspect that any of them had “feelings” for my little angel. (To be continued…)