Editor’s note: Volume 3 of Deschner’s opus deals with forgery and brainwashing in the Ancient Church.

But since Volume 1 we get a taste of the flavour of how the early Christians grossly exaggerated the ‘gentile’ sins (see my hatnote on the previous instalment of this series), just as presently the fate of the Jews in World War II has been grossly exaggerated.

In the hostile takeover of Aryan civilisation, be the Ancient World or today, the art of making whitey feel guilty has been a formidable weapon. No wonder why Hitler called Christianity ‘the Bolshevism of the Ancient World’.

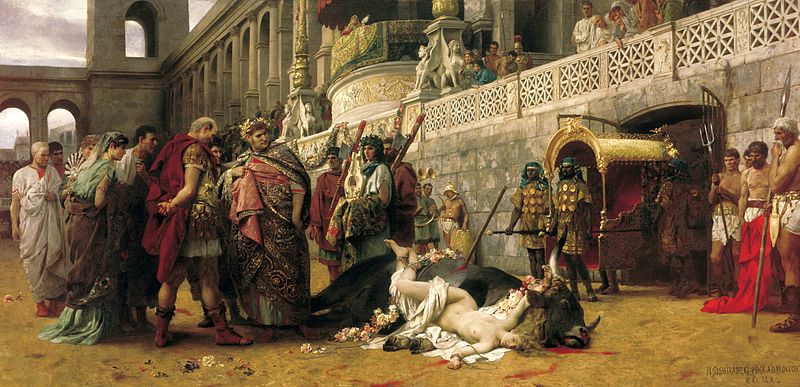

A Christian Dirce, by Henryk Siemiradzki. A Christian woman is martyred under Nero in this re-enactment of the myth of Dirce.

______ 卐 ______

Below, abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz

Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums

(Criminal History of Christianity)

The persecutions against Christians in the mirror of ecclesiastical historiography

The accusations against the pagans began, precisely because of these persecutions, presented with enormous exaggeration. And in that vein we have followed well into the 20th century, when it is still written that during the 1st century Christianity was ‘bathed in its own blood’, ‘innumerable hosts of heroic characters’ are weighed, and ‘the second century is recalled by the procession of those bearing on the forehead the bloody mark of martyrdom’ (Daniel Rops); although, at times, it must be confessed that ‘they were not millions’ (Ziegler).

The most serious and undisputed investigations estimate the number of Christian victims sometimes at 3,000, others at 1,500 for the total of three centuries of persecution. A Christian as worthy of respect as Origen, who died in 254 and whose father was a martyr, and who suffered torture himself, says that the number of witnesses of blood of Christianity was ‘small and easily re-countable’.

In effect, it happens that most of the ‘martyrs’ acts are forgeries, that many pagan emperors never persecuted Christianity, and that the State did not meddle with Christians because of their religion. In fact, the civil service of the old regime treated them with enough tolerance. They granted them deferrals, they ignored the edicts; tolerated deceptions, set them free, or taught them the legal arguments with which they could free themselves from persecution without abjuring their faith. Those who denounced themselves were sent home, and even often they indifferently endured the provocations.

In the first half of the 4th century, however, Bishop Eusebius, ‘father of ecclesial historiography’, is inexhaustible in inventing stories about the wicked pagans, the terrible persecutors of Christianity. To this theme he devotes the whole eighth book of his Ecclesiastical History, from which surely one can affirm what a scholar of the 9th and 10th volumes of this work said (which is almost the only available source on the history of the Church in the antiquity): ‘Emphasis, periphrasis, omissions, half truths, and even falsification of the originals replace the scientific interpretation of reliable documents’ (Morreau).

We see there how, again and again, the wicked pagans—actually our bishop Eusebius—torture Christians with lashes, ‘those really admirable fighters’; they rip their flesh out, break their legs, cut their noses, ears, hands and other members. Eusebius throws vinegar and salt in the wounds, heaves sharpened reeds under the nails, burns backs with molten lead, fries the martyrs in grills ‘to prolong the torment’. In all these situations and many more, the victims retain their integrity, even their good humour: ‘They sang praises to the God of heaven and gave thanks to their torturers, to the last breath.’

Other believers, Eusebius informs us, were drowned in the sea ‘by order of the servants of the devil’, or crucified, or beheaded ‘sometimes in number of up to a hundred men, young children [!] and women in a single day… The executioner’s sword mended, and the tired executioners were forced to relieve themselves’.

Others were thrown ‘at the anthropophagous beasts’, to be devoured by wild boars, bears, panthers. ‘We have been eyewitnesses [!] and we have seen how, by the divine grace of our Redeemer Jesus Christ, of whom they bear witness, when the beast was ready to leap it receded again and again, as repulsed by a supernatural force’.

The bishop tells of the Christians (five in all) who were to be ‘shattered by an enraged bull’: ‘As much as he dug with its hooves and delivered goring from one side to the other, spurred by red irons, snorting with rage, the Divine Providence did not allow any harm on them’.

Christian historiography!

In one passage, Eusebius mentions ‘a whole village of Phrygia inhabited by Christians’, whose inhabitants, ‘including women and children’, were burned alive… but unfortunately he forgot to tell us the name of the village in question.

It is a habitual feature of Eusebius to get by without the details despite having been, as he says, an eyewitness. He prefers to speak of ‘innumerable legions’, of ‘great masses’ exterminated partly by the sword, sometimes by fire, ‘countless men and women and children’ who died ‘in various ways by the doctrine of our Redeemer’. ‘Their display of heroism defy description’.

During the persecution of 177 in Gaul under Marcus Aurelius (161-180), the philosopher-emperor whose Meditations Frederick II of Prussia admired, Eusebius tells us that there were ‘tens of thousands of martyrs’. However, the martyrology of the Gallic persecution under Marcus Aurelius totals… 48 victims. Of all these, the so-quoted Lexikonfür Theologie und Kirche only recounts eight, ‘St Blandina with Bishop Photinus and six of his followers’. On the contrary, the number of pagan victims in Gaul was, in later centuries, ‘far superior’ (C. Schneider).

On the persecution by Diocletian, the bloodiest (against the express will of this remarkable emperor), Eusebius could not regret—or perhaps it would be better to say to celebrate, since the leaders of the Church always considered providential the persecutions, and popes of our 20th century have affirmed it—that the victims would have counted by tens of thousands, since many eyewitnesses still lived. Persecutions are a stimulus. They foster the unity of the persecuted and are the best propaganda imaginable of all time. Eusebius, author of a chronicle ‘on the martyrs of Palestine’ wrote in his Ecclesiastical History: ‘We know the names of those who stood out in Palestine’ and cites a total of 91 martyrs, and not ‘tens of thousands’.

In 1954, De Ste Croix reviewed for the Harvard Theological Review the figures of the ‘father of Christian historiography’ and only sixteen Palestinian martyrs were found, and that for the worst of the persecutions, which lasted there ten years, bringing the average not even two victims a year. In spite of all this, one of Eusebius’s modern panegyrists rejects the conclusion that Eusebius lacked ‘scientific scrupulousness’ (Wallace-Hadrill).