Editor’s note: After reading the stories of the white race of Pierce and Kemp, it is obvious that, once the ‘Aryan problem’ is understood, the most practical thing is to exterminate the conquered non-whites instead of using them.

The Aryan problem consists of seeing as capital (slaves) a lower species of humans whose biology allows them to de-code the Aryan DNA and produce fertile mongrels if crossbreeding with them. Since sexual lust is natural among whites, this was precisely how the Roman Empire declined and fell.

In this section we see what Deschner says about the son of Constantine who inherited the empire. Like his father, he forbade Jews from any activity involving slaves: ‘That’s when the Jews’ dedication to financial activities began’. The Christian Constantius practised scorched-earth policies against his Germanic neighbours but not against the Semites at home! In our days the Jewish dominion of the financial sector has its roots in the non-exterminationist, misconceived policies of the Roman emperors. Deschner wrote:

______ 卐 ______

Constantius and his Christian-style government

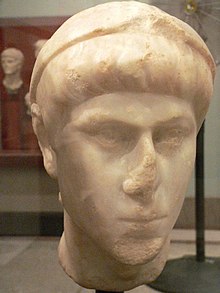

(Bust of Constantius II.) Not content with these perfidious massacres, the ‘religiosissimus imperator’ undertook continuous wars against the Alamanni, the Sarmatians, the Persians and other nations; always very cautious, slow but conscientious, always preparing the campaigns thoroughly, from Mesopotamia to the Rhine. He used to leave only a scorched earth behind him.

(Bust of Constantius II.) Not content with these perfidious massacres, the ‘religiosissimus imperator’ undertook continuous wars against the Alamanni, the Sarmatians, the Persians and other nations; always very cautious, slow but conscientious, always preparing the campaigns thoroughly, from Mesopotamia to the Rhine. He used to leave only a scorched earth behind him.

That politician of whispering and cabinet, in whose court an extraordinary accumulation of bishops met, had very intimate relations with religion. ‘The first ruler who considered himself enthroned by the grace of God’ (Seeck), and who liked to be called officially lord of the whole earth and ‘my eternity’ (aeternitatem meam), was convinced of being an instrument appointed by the Most High and enjoyed the special protection of an angel, whose vague and vaporous contours he even thought he saw sometimes, floating in the air. He practiced chastity with more conviction than his brother, the fan of the ephebes.

This emperor favoured the Christian priests even more than his father, and confirmed, enlarged and multiplied the privileges granted.

If Constantine had dispensed them from the artisanal contribution, Constantius forgave them the territorial contribution and the tax for the use of mail. In the year 355, he ordered that the bishops could not be tried by the common courts, ‘to avoid false testimonies promoted by the fanatical spirits’. And not only did he exempt them from common services, but their wives and children as well as their servants of both sexes would be exempt in perpetuity from all kinds of taxes and benefits on behalf of the State. However, and this is typical of all ecclesiastical history, such concessions only served to make the clergy claim even more privileges.

Constantius, who was not baptized until the end of his life, as his father had done (and in that case, too, being the Arian officiant Eudocium of Antioch), was an Arian Christian. Father Athanasius, his main adversary, includes him in the large list of great Biblical sinners: he calls him perjurer, unjust, irresponsible and worse than the pagan emperors, leader of the impious, accomplice of bandits and Antichrist. ‘There is hardly room for insults worse than those lavished by Athanasius’ (Hagel).

Like his father, Constantius used Christianity as an instrument of his politics and not the other way around. Therefore, as soon as he saw himself as the sole emperor, his first concern was the unity of the Church, although unlike his father, he preferred to look for it in the Arian patriarchs. Hence he banished one after another of numerous Catholic patriarchs, including Athanasius, Paul of Constantinople and Hilary de Poitiers.

Others, like Pope Liberius and Hosius of Corduba, suffered the weight of his authority: ‘My will must be law for the Church’, he explained to those gathered in Milan in 355. ‘You will obey, or you will be banished’. At the same time persecution continued against the Donatists of Africa that Constantine did not initiate, and even proceeded against a sect of Arianism, that of the Anomoeans, seventy of whose bishops are said to have been exiled by his order.

With the Jews, Constantius was even more brutal than his father. A law of the year 339, which calls them a ‘nefarious sect’ and calls ‘markets’ their places of assembly, prohibits under pain of death at the stake to make it difficult for any Jew to pretend to convert to Christianity.

Now, even if the Jews were authorized to become Christians, the Christian who converted to Judaism faced the ‘deserved punishment’, according to the emperor, of confiscation of all his property. He forbade marriages between Christians and Jews; in particular, he persecuted the entry of women into the Hebrew communities with the death penalty.

The Jews could not buy slaves, even if they were pagans, under penalty of confiscation of property, or death penalty if they dared to circumcise them. Consequently, he forbade them any economic activity whose exploitation necessitated the employment of slaves; surely, that’s when the Jews’ dedication to financial activities began, which made them even more hated. The repression was severe, especially with the Jews of Palestine, after an insurrection that was bloody crushed.

The attitude of Constantius against the pagans was also very hard, probably instigated by the Christian party.