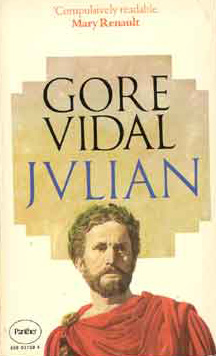

Julian presiding at a conference of Sectarians

(Edward Armitage, 1875)

I remained the rest of that year at Constantinople. I had a sufficient income, left me by my grandmother who had died that summer. I was allowed to see her just before her death, but she did not recognize me. She spoke disjointedly. She shook with palsy and at times the shaking became so violent that she had to be strapped to her bed. When I left, she kissed me, murmuring, “Sweet, sweet.”

By order of the Grand Chamberlain I was not allowed to associate with boys my own age or, for that matter, with anyone other than my instructors, Ecebolius and Nicocles, and the Armenian eunuch. Ecebolius is a man of much charm. But Nicocles I detested. He was a short, sparse grasshopper of a man. Many regard him as our age’s first grammarian. But I always thought of him as the enemy. He did not like me either. I remember in particular one conversation with him. It is amusing in retrospect. “The most noble Julian is at an impressionable period in his life. He must be careful of those he listens to. The world is now full of false teachers. In religion we have the party of Athanasius, a most divisive group. In philosophy we have all sorts of mountebanks, like Libanius.”

That was the first time I heard the name of the man who was to mean so much to me as thinker and teacher. Not very interested, I asked who Libanius was.

“An Antiochene—and we know what they are like. He studied at Athens. Then he came here to teach. That was about twelve years ago. He was young. He was bad-mannered to his colleagues, to those of us who were, if not wiser, at least more experienced than he.”

Nicocles made a sound like an insect’s wings rustling on a summer day—laughter? “He was also tactless about religion. All the great teachers here are Christian. He was not. Like so many who go to Athens (and I deplore, if I may say so, your desire to study there), Libanius prefers the empty ways of our ancestors. He calls himself a Hellenist, preferring Plato to the gospels, Homer to the old testament. In his four years here he completely disrupted the academic community. He was always making trouble. Such a vain man! Why, he even prepared a paper for the Emperor on the teaching of Greek, suggesting changes in our curriculum! I’m glad to say he left us eight years ago, under a cloud.”

“What sort of cloud?” I was oddly intrigued by this recital. Oddly, because academics everywhere are for ever attacking one another, and I had long since learned that one must never believe what any teacher says of another. “He was involved with a girl, the daughter of a senator. He was to give her private instruction in the classics. Instead, he made her pregnant. Her family complained. So the Emperor, to save the reputation of the girl and her family, a very important family (you would know who they are if I told you, which I must not)… the Augustus exiled Libanius from the capital.”

“Where is Libanius now?”

“At Nicomedia, where as usual he is making himself difficult. He has a passion to be noticed.” The more Nicocles denounced Libanius, the more interested I became in him. I decided I must meet him. But how? Libanius could not come to Constantinople and I could not go to Nicomedia. Fortunately, I had an ally.

I liked the Armenian eunuch Eutherius as much as I disliked Nicocles. Eutherius taught me court ceremonial three times a week. He was a grave man of natural dignity who did not look or sound like a eunuch. His beard was normal. His voice was low. He had been cut at the age of twenty, so he had known what it was to be a man. He once told me in grisly detail how he had almost died during the operation, “from loss of blood, because the older you are, the more dangerous the operation is. But I have been happy. I have had an interesting life. And there is something to be said for not wasting one’s time in the pursuit of sexual pleasure.”

But though this was true of Eutherius, it was not true of all eunuchs, especially those at the palace. Despite their incapacity, eunuchs are capable of sexual activity, as I one day witnessed, in a scene I shall describe in its proper place.

When I told Eutherius that I wanted to go to Nicomedia, he agreed to conduct the intricate negotiations with the Chamberlain’s office. Letters were exchanged daily between my household and the palace. Eutherius was often in the absurd position of writing, first, my letter of request, and then Eusebius’s elaborate letter of rejection. “It is good practice for me,” said Eutherius wearily, as the months dragged on.

Shortly after New Year 349 Eusebius agreed to let me go to Nicomedia on condition that I do not attend the lectures of Libanius. As Nicocles put it, “Just as we protect our young from those who suffer from the fever, so we must protect them from dangerous ideas, not to mention poor rhetoric. As stylist, Libanius has a tendency to facetiousness which you would find most boring. As philosopher, he is dangerously committed to the foolish past.” To make sure that I would not cheat, Ecebolius was ordered to accompany me to Nicomedia.

Ecebolius and I arrived at Nicomedia in February 349. I enjoyed myself hugely that winter. I attended lectures. I listened to skilled Sophists debate. I met students of my own age. This was not always an easy matter, for they were terrified of me, while I hardly knew how to behave with them.

Libanius was much spoken of in the city. But I saw him only once. He was surrounded by students in one of the porticoes near the gymnasium of Trajan. He was a dark, rather handsome man. Ecebolius pointed him out, saying grimly, “Who else would imitate Socrates in everything but wisdom?”

“Is he so bad?”

“He is a troublemaker. Worse than that, he is a bad rhetorician. He never learned to speak properly. He simply chatters.”

“But his writings are superb.”

“How do you know?” Ecebolius looked at me sharply.

“I… from the others here. They talk about him.” To this day Ecebolius does not know that I used to pay to have Libanius’ lectures taken down in shorthand. Though Libanius had been warned not to approach me, he secretly sent me copies of his lectures, for which I paid him well.

“He can only corrupt,” said Ecebolius. “Not only is he a poor model for style, he despises our religion. He is impious.”